SPACE December 2025 (No. 697)

The erosion of the genre boundaries across the arts – and indeed across many other fields – has become a defining phenomenon of our time. Hybridity, diversification, and decentralisation no longer signal rupture but rather the unremarkable or routine. Exhibition spaces, too, have expanded beyond the conventional white cube, stretching into emergent project spaces, the metaverse, VR, and various online realms, forming an open ecosystem that embraces artistic practices across mainstream and non-mainstream lines. ‘Wreath and Towel’ is one such platform: an online and offline exhibition initiative that welcomes texts of many kinds, unfolding them into layered, spatial forms. Its contributors include analytic aestheticians, comics critics, designers, writers of independent publications, as well as researchers of spatial culture, and contributors who work in areas such as coding, or sign-language literature—anyone who conveys ideas through alternative textual methods. Within Wreath and Towel, each contributor is intended to be newly ‘read’ through their own idiosyncratic mode. What follows is an exploration of the platform that is rewriting the rules of contemporary exhibition culture. Editor

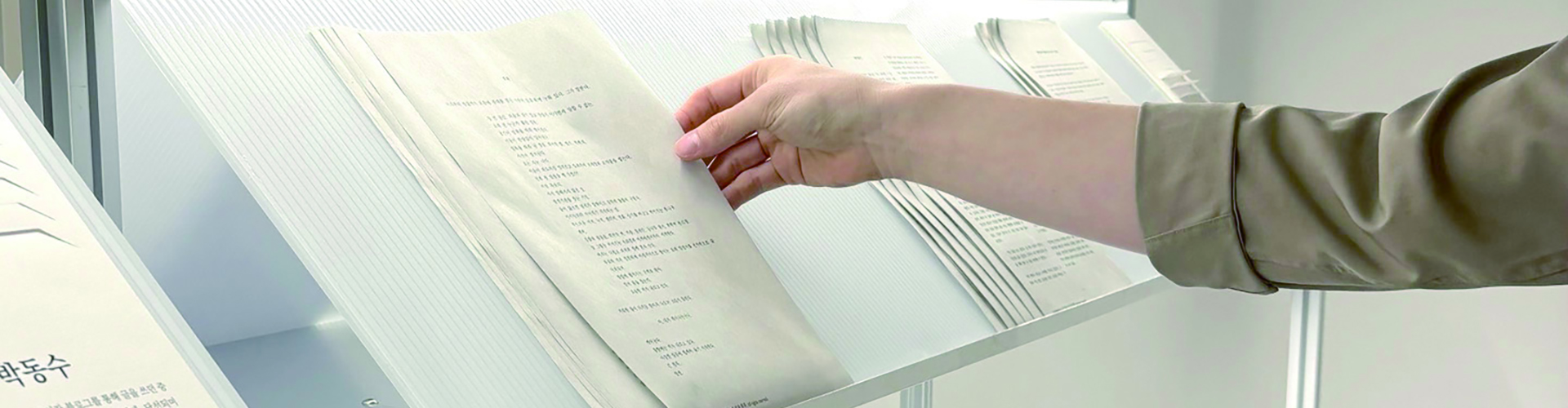

Exhibition view of ‘Text Buffet’ (2024)

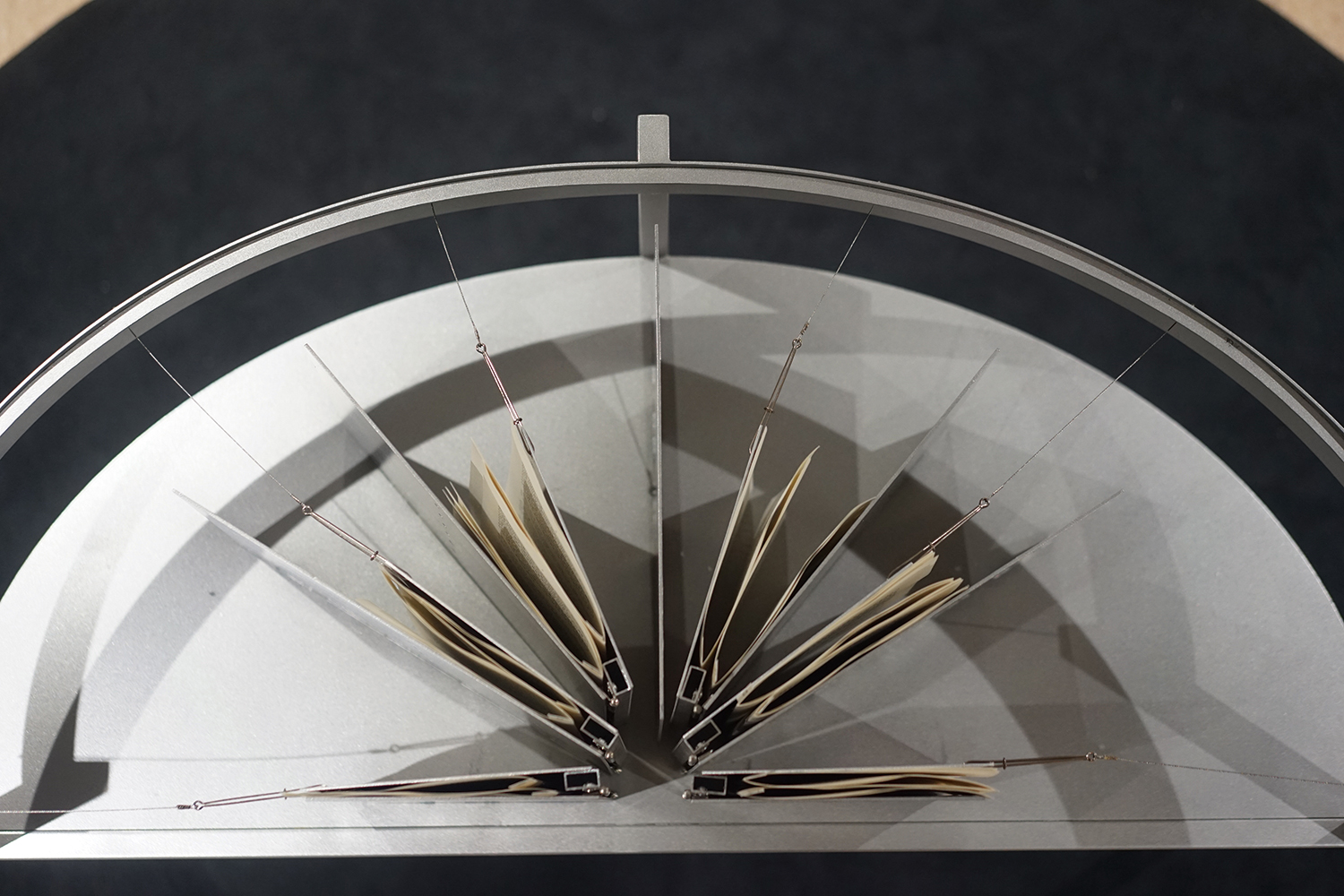

‘Parts Hypothesisum’ (2025)

Interview Lee Yehyun director, Wreath and Towel × Kim Hyerin

Kim Hyerin (Kim): What prompted you to establish and operate an exhibition platform?

Lee Yehyun (Lee): I studied Fine Art in the Netherlands and Belgium during my undergraduate years. However, I eventually withdrew from this sphere, mainly because I struggled to see a sustainable economic future in conventional artistic practice. Upon returning to Korea, I worked at a print shop and later as a curatorial researcher at a private art museum. From around 2010, I became fascinated by the small-scale exhibition venues often referred to as ‘new independent spaces’, and I began visiting them across Seoul. In attempting to find ways to break free from the rigidity of existing exhibition formats, I opened an offline space in Huam-dong in 2021. There, I tested exhibition practices that departed from the expected roles and forms of contemporary art spaces. We avoided signage, posters or leaflets, and instead prioritised direct encounters—welcoming visitors personally and placing an emphasis on relational engagement. After operating there for two years, I moved to the current location at the UnWoo Art Museum in Seongbuk-dong, where the platform was oriented more explicitly around text.

Kim: What led you to conceive of a text-centred platform?

Lee: Text has the ability to traverse genres, and when employed as an artistic medium, it can expand what an exhibition space can be. Running the space in Huam-dong, I encountered many practitioners who worked with text critics, writers of proposals, and people operating across different textual fields. There should be exhibitions for them too. This impulse developed into ‘Text Buffet’ (2021–2022, 2024), an exhibition where visitors selected texts as if choosing dishes from a buffet. They placed manuscripts on trays, arranged them in their own sequence, read them in combination, and left them behind when they exited. The exhibition positioned text not as reading material but as a temporal artwork, experienced within a bounded space and time—thus distinguishing it from conventional modes of reading. From that point onwards, text became a continuous catalyst for exhibitions.

Exterior view of UnWoo art Museum

‘Text Buffet’ (2024), visitors can pick and choose the text, buffet-style.

Kim: Text does not inherently require an exhibition space. One could argue that publishing is its natural home.

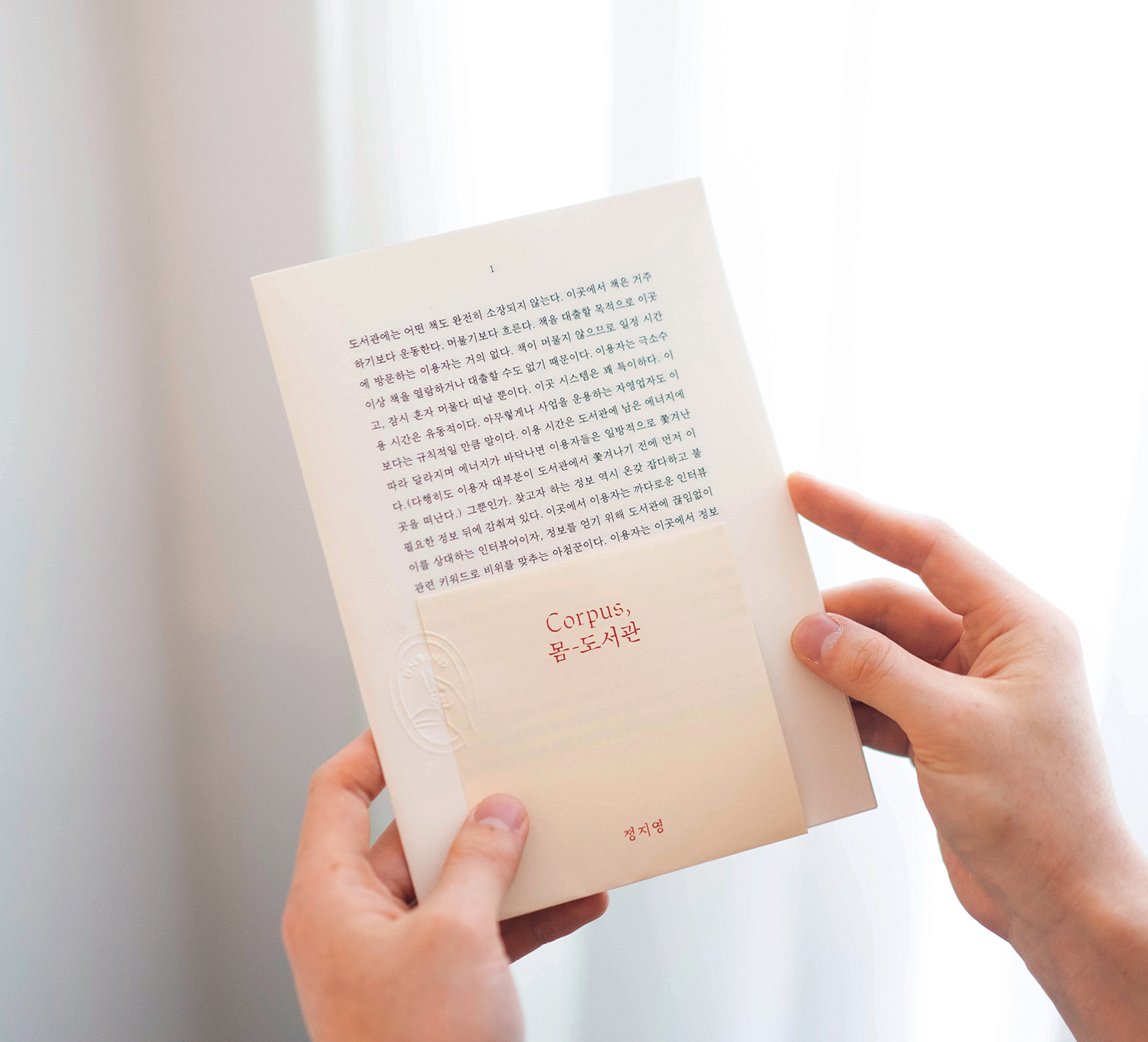

Lee: Coming from a background in the visual arts, I have always believed that text can become a visible, spatial artwork in its own right. To achieve this, I wanted to guide visitors towards viewing rather than reading by using alternative modes of reception as a curatorial framework, even as a form of choreography. I also wanted text to become a more active medium. Rather than ending its life as a printed book, I wanted to showcase its entire circulation process. At Wreath and Towel, text undergoes different stages of experience and transformation. Each work requires its own optimised form, and we seek to escape inherited formats. Recently, we have begun publishing loose-leaf text series under the title UNBIND, exploring ways for the exhibition to extend beyond the physical gallery.

Kim: What informed the choice of name, Wreath and Towel?

Lee: An exhibition comes with a set opening period, and from the moment it opens, a particular relationship forms between the artist and society. This process reminded me of school sports days or retirement ceremonies—events in which commemorative gifts are exchanged, such as towels embroidered with event dates or congratulatory wreaths. I felt these objects were metaphorically aligned with the dynamics of an exhibition.

‘Parts Hypothesisum’ (2025), Wang Eunji, CT01, 980 × 425 × 800 mm

Parts used in ‘Parts Hypothesisum’ to slide sideways and reveal hidden words

Kim: How do you run the offline space?

Lee: During any exhibition, the operator is always present. At its core, an exhibition is a site where artists and visitors enter into relation. Showing works and walking away feels insufficient. If exhibitions are forms through which the artist’s desire for self-articulation and professional growth becomes visible, then the space must shoulder responsibility for facilitating this. During ‘Text Buffet’, for example, I met each participating contributor and shaped the presentation through conversation, relaying these discussions to visitors. We also frequently hold open conversations with visitors about the roles and responsibilities of exhibition spaces. The exhibitions here tend to produce a great deal of dialogue.

Kim: Who tends to visit the space?

Lee: Friends of participating artists, university students in the arts, and designers from various fields. Graphic designers and typographers visit particularly often. Small, experimental art spaces attract people already interested in artistic practice. Depending on the exhibition, whether it concerns design or more experimental work, different communities stop by.

UNBIND loose-leaf text series

Kim: What is the usual process behind mounting an exhibition here?

Lee: Sometimes an exhibition evolves from conversations with visitors. If we sense a shared direction, we identify a theme that excites us and develop it into an exhibition. The recent show, artist Yoon Marie ‘Soma’ (2025), originated precisely this way. During our conversation, she mentioned she had written a text—one she wished to present yet not have permanently recorded. Torn between the impulse to write, the refusal to leave a trace, and the desire to share the work nonetheless, she proposed ‘verbal publication’, a practice first attempted by a member of Oulipo, in which the act of reading itself replaces publication. We captured this in the gallery setting. Another example is furniture designer Wang Eunji’s ‘Parts Hypothesisum’ (2025). Hearing her thoughts on furniture, informed by text, we developed an exhibition that explores the shifting boundary between text and object form. Our approach varies each time; we rarely present exhibitions solely of artworks. The artist is always regarded as a co-curator.

Kim: You have also staged exhibitions about exhibition-making itself, such as ‘Locus Solus, for Unrealised Exhibition Proposals’ (2022).

Lee: That exhibition was inspired by Raymond Roussel’s Locus Solus (1914)—a speculative, quasi-science-fiction novel characterised by obsessively realistic detail. I was intrigued by the idea that images not found in reality could become convincing through textual structuring. We brought this literary mechanism into dialogue with exhibition proposals that were never realised. Visitors entered the space, viewed Locus Solus, listened to an explanation of the curatorial premise, and then read the unrealised proposals—imagining the exhibitions for themselves.

Kim: You solicit submissions online as well as invite writers directly. How do you make selections?

Lee: Initially, I considered establishing criteria. But criteria inevitably act as a form of censorship and exclusion. Instead, we look for works that depart from conventional genres—texts that feel fresh and conceptually playful. Regardless of whether a submission is selected, I meet the contributor in person, discuss how I read the text, and talk about potential directions for development.

Exhibition view of ‘Text Buffet’ (2021 – 2022), held in Huam-dong

‘Locus Solus, for Unrealized Exhibition Proposals’ (2022), trolley containing the exhibition proposals

Kim: Alongside online archiving and physical text-based documentation, you also operate other forms of archiving.

Lee: In Huam-dong, we created an ‘archivist’ system. Because one of our rules was to avoid photographic documentation, we asked visitors whether they would serve as archivists. Those who agreed received a name card, and their names were listed on our website. Their memories – rather than images – formed the record of the exhibition. It was a deliberate shift away from transparent, image-driven documentation towards oral, experiential transmission.

Kim: Are you currently working on any archival projects?

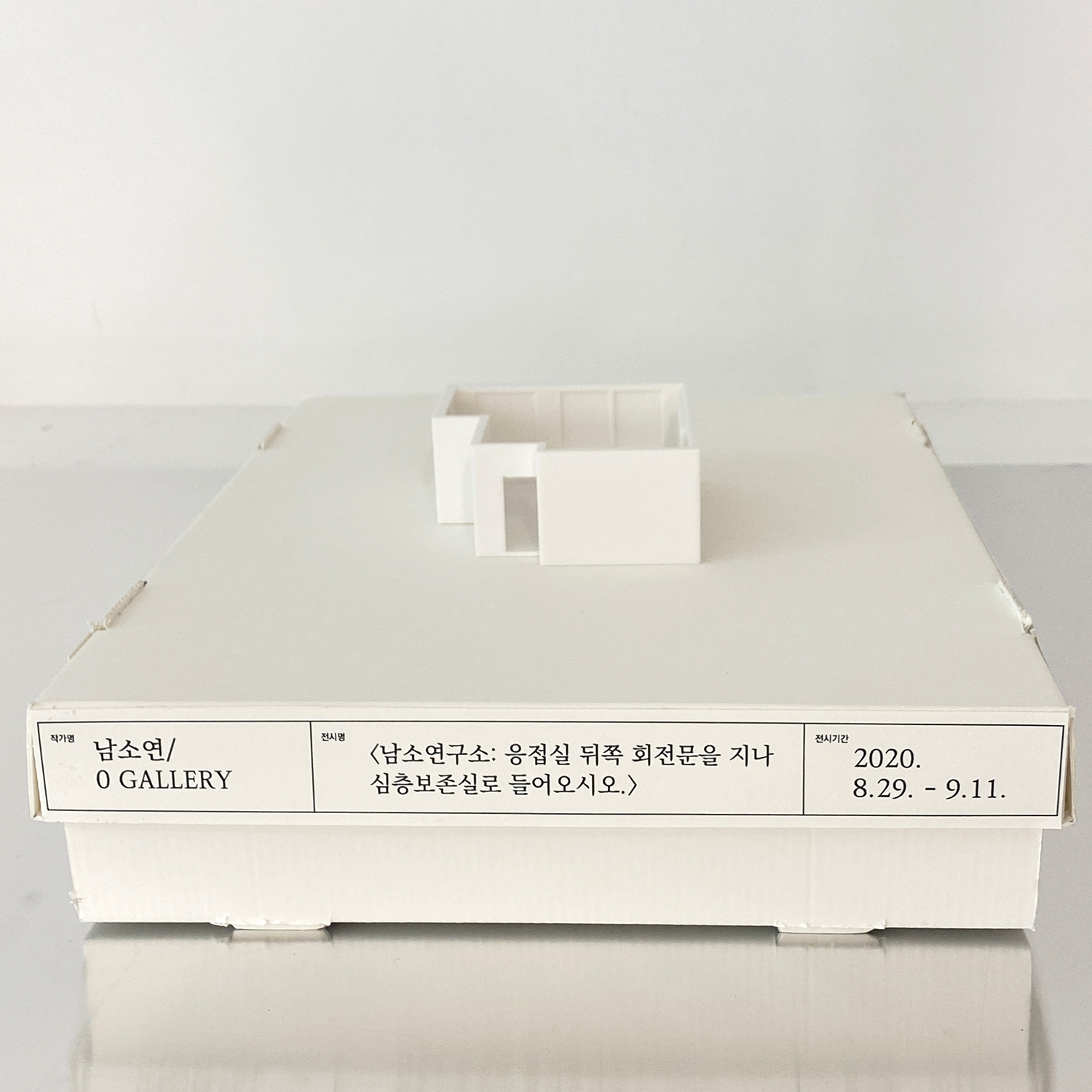

Lee: Yes—It is a personal project. I’m creating archive boxes dedicated to exhibition spaces that have disappeared. Many new independent spaces vanish simply because their leases expire, and they become regarded as temporary or disposable. I found this troubling, so I began preserving them. Based on my own experiences of each space, I create 3D diagrams, record my memories of exhibitions and spatial movements, and trace architectural data such as floor area through official registries. I document what the space was like, who ran it, how it operated, and even the amount of the rent. I’ve produced about four such archive boxes so far, including one for the Huam-dong space. In a sense, I am building a ‘collective cemetery of exhibition spaces’.

Archive box of disappeared exhibition spaces

Scene from the verbal publication of ‘Soma’ (2025) ©Park Juwon