SPACE September 2025 (No. 694)

In the early spring of 2023, while preparing a workshop for the International Architecture Exhibition at the Venice Biennale as a ‘related population’ of Gunsan, I first encountered the Project Re\Turning Gunsan (hereinafter Re\Turning Gunsan). The theme of that workshop was the dismantling of the roofs of old jeoksan (Japanese-colonial-era) houses in Gunsan and returning them to nature. Rather than filling the shrinking provincial city with new programmes in the face of demographic decline and the erosion of its community, the idea was to contemplate strategies by which parts of the city might revert to nature. The outcome of the workshop was the design of a dismantling process that, using primitive tools, would accelerate weathering. This became an experiment jointly conducted by permanent residents – local activists seeking ways to revitalise the city – and by temporary related population participating from the outside.

The Re\Turning Gunsan’s initiative, by contrast, was conceived to harness the native network of Gunsan-born individuals as a foundation for long-term revitalisation. Its ambition was to establish a solid and sustainable anchor for urban regeneration. Over more than five years, the project extended its networks across the nation, providing a platform that embraced both permanent residents and related populations. Even before the facilities formally opened, the site had already become a gathering place. Skilled professionals expected to operate the facilities and ordinary visitors alike, drawn by the anticipation of a new kind of space, began to assemble there. Unlike one-off municipal regeneration projects that merely exhaust budgets, or commercial spatial-branding exercises that cling nostalgically to retrogressive strategies and end up producing ‘junkspace’ doomed to imminent disappearance, this network was the animating energy that gave life to Re\Turning Gunsan.

The character of this human resource mirrors the temporality embedded in Gunsan’s historic blocks. These blocks embody more than a century of archaeological layering, beginning with the superimposition of colonial urban structures and residential typologies upon indigenous life during the period of the port’s opening, and the subsequent transformation and reappropriation after liberation. They are sites where the rigid typologies of colonial architecture coexist with the everyday customs that sought to subvert and adapt them. In this sense, the Re\Turning Gunsan may be read as an experiment in crafting recipes between typology and custom. Participants embodied these layered temporalities: a Gunsan native restaurateur who continues to reside in the city, an architect born in Gunsan returning as a relational inhabitant to engage with the project, and a curator traveling from Finland to direct its orchestration and management. Each, in their different ways, entered into a relation with the temporal strata of the city, converging to ‘cook’ the imperial remnants left behind by the colonial builders.

The Colonial Planner of Gunsan: Asayama Kenzo

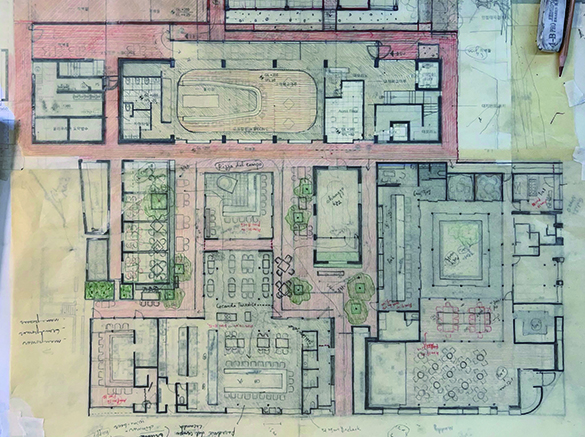

The Re\Turning Gunsan takes as its raw material the urban block structures of the old city centre, first laid out as concession districts during the colonial port-opening era. To understand this, one must revisit the origins and transformations of Gunsan’s historic blocks. Among the relevant research, the paper ‘Installation of Japanese Consulate in Gunsan and activities by Chief Secretary during the port opening period (from 1899 to 1906)’▼1 is particularly revealing, for it identifies the individual who conceived and executed the original plan for Gunsan’s city centre.

According to the study, the planning and implementation of the colonial city were carried out by Asayama Kenzo (淺山顯藏), a Japanese chief student interpreter assigned to the Gunsan consular branch. From the mid-1870s to the early 1900s, Asayama worked in Korea as an interpreter, directly witnessing such pivotal historical events as the Imo Incident and the Gapsin Coup. Recognised for his expertise as a ‘Korea specialist’, he was appointed head of the consular branch in Gunsan. Immediately upon arrival, he undertook a precise survey of the Japanese concession at the port, establishing its territorial base. He then demarcated roads, blocks, parcels, and boundaries, instituting a cadastral system for the Japanese settlement. Although Asayama did not personally design the houses and roads, the work was carried out under his supervision. The urban prototype for Gunsan, a layout that we still recognise today, was formed during this period.

The optical surveying techniques used inscribed the land with linear and regular divisions. Landownership and boundaries within the concession, once ambiguous, were converted into manageable modern units. These were distributed among Japanese settlers as residential, commercial, and public plots, soon to be filled with Japanese-style houses. (...)

_

1 Choi Boyoung, ‘Installation of Japanese Consulate in Gunsan and activities by Chief Secretary during the port opening period (from 1899 to 1906)’, The Journal of Jeonbuk Studies 1(2019).

You can see more information on the SPACE No. September (2025).

Lee Chihoon

Lee Chihoon co-founded SoA, an architectural firm working on projects concerned with environment construction at various scales based on analysis from the social conditions of architecture and urbanism. SoA was selected as the winner of the 2015 Young Architects Program and the Korea Young Architects Award, nominated as one of the AR Emerging Architecture 2016 Finalists, and won the Kim Swoo Geun Preview Award (2016), Korea Design Award (2021), and the Korean Association for Architecture History Award (2023).

0