SPACE March 2025 (No. 688)

Poster of ‘Little Toad Little Toad: Unbuilding Pavilion’ Poster design by Kim Yuna

In 2025, marking the 30th anniversary of the Korean Pavilion’s construction in the Giardini, the professional architectural curation collective CAC (Curating Architecture Collective) was appointed as curator. When CAC entered the competition to select the curator for the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2025, they proposed the theme ‘House of Trees’, highlighting trees as a critical element in the history of Venice, the Giardini, and the Korean Pavilion itself to herald this landmark anniversary. That initial concept has since evolved into what is now titled ‘Little Toad Little Toad: Unbuilding the Pavilion’. We sat down with CAC to learn about their plans for the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2025, including their earliest ideas for the exhibition, how those ideas took shape over roughly a year of preparations, and how the final exhibition will ultimately be presented.

interview Chung Dahyoung, Kim Heejung, Jung Sungkyu co-directors, CAC × Kim Bokyoung

Kim Bokyoung: This year’s exhibition at the Korean Pavilion of the Venice Biennale shines a spotlight on the untold stories of the Korean Pavilion’s construction and design, re-evaluating a space that has often been underestimated as an exhibition venue. At the same time, by rediscovering the pavilion’s sustainability credentials, it broadens the narrative from the Korean Pavilion to a universal story that could be applied not only to the Giardini – where the national pavilions are located – but to the Venice Biennale as a whole, and ultimately to the city of Venice. As an architectural curator, you likely had an abundance of ideas and angles you wanted to explore. What led you, at this particular moment, to conceive and plan this kind of exhibition?

Chung Dahyoung: All three of us share the same interests, and as architectural curators, our focus on a building’s lifespan or its temporal dimension naturally shaped this exhibition. We often concentrate only on the moment a building is completed, then lose interest. While the fact that the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale is celebrating its 30th anniversary is significant, we also wanted to consider its entire lifespan, from the past through the ensuing three decades. Moreover, we believe a building’s lifespan continues even after demolition. This exhibition grew out of our ongoing reflections following completion, the time before completion, and the time after a building disappears. I suspect we will continue exploring this more elastic notion of time in future exhibitions and research.

Part of the commissioned illustration by Jung Jinho ©Jung Jinho

Kim Bokyoung: After winning the competition, you spent about a year planning the exhibition, including a site visit to Venice. During that process, the theme evolved from ‘House of Trees’ to what is now called ‘Little Toad Little Toad’. Why and how did the exhibition’s concept change?

Kim Heejung: The turning point came at a roundtable titled ‘The Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale: Current Issues and Possibilities for Designing a New Future’, hosted by the Arts Council Korea in 2023. That event was organised after Franco Mancuso, one of the architects who co-designed the Korean Pavilion, donated materials related to the pavilion’s design. Several former directors and curators also attended. When we looked at drawings from the pavilion’s design phase, we noticed that the trees and the building were depicted on an equal footing in many of them. We even joked that they looked more like plans for trees than plans for a pavilion, which made us interrogate the pavilion’s relationship with trees. After being appointed as curators, we revisited the Korean Pavilion in Venice with the artists, and we realised that the site condition of trees dotted across the space is not unique to the Korean Pavilion. It is part of a shared logic in the Giardini, where the other national pavilions are located. That realisation led us to see that trees could be a universal theme, one that could connect the Korean Pavilion with other national pavilions.

Chung Dahyoung: ‘House of Trees’ does touch on the core theme of our exhibition, but the title itself feels neutral and doesn’t clearly reveal our position. That was one reason we decided to change it. Some people even thought it was an exhibition about wooden houses. (laugh)

From this perspective, we wanted a clear focal point in which visitors could engage with the exhibition. That led us to use a fable-like framework to express the curator’s viewpoint. We felt this narrative approach could link the curator-led research to the artists’ work. Conveniently, the lyrics of Little Toad Little Toad offer up an analogy between an old house and a new house, along with a sense of crisis about the identity of home itself. Instead of treating the Korean Pavilion as a neutral white cube, we wanted to see it as a more organic entity—a ‘home for the exhibition’. In this context, Little Toad Little Toad aligns closely with what we hoped to communicate. Furthermore, toads are symbols of renewal and transformation in both Eastern and Western cultures. We thought using this fable-like device, viewing the exhibition through the toad’s eyes, would make the exhibition much more intriguing. If you look at the illustrations by Jung Jinho (picture book artist), you’ll get a better sense of how the toad’s perspective ties everything together.

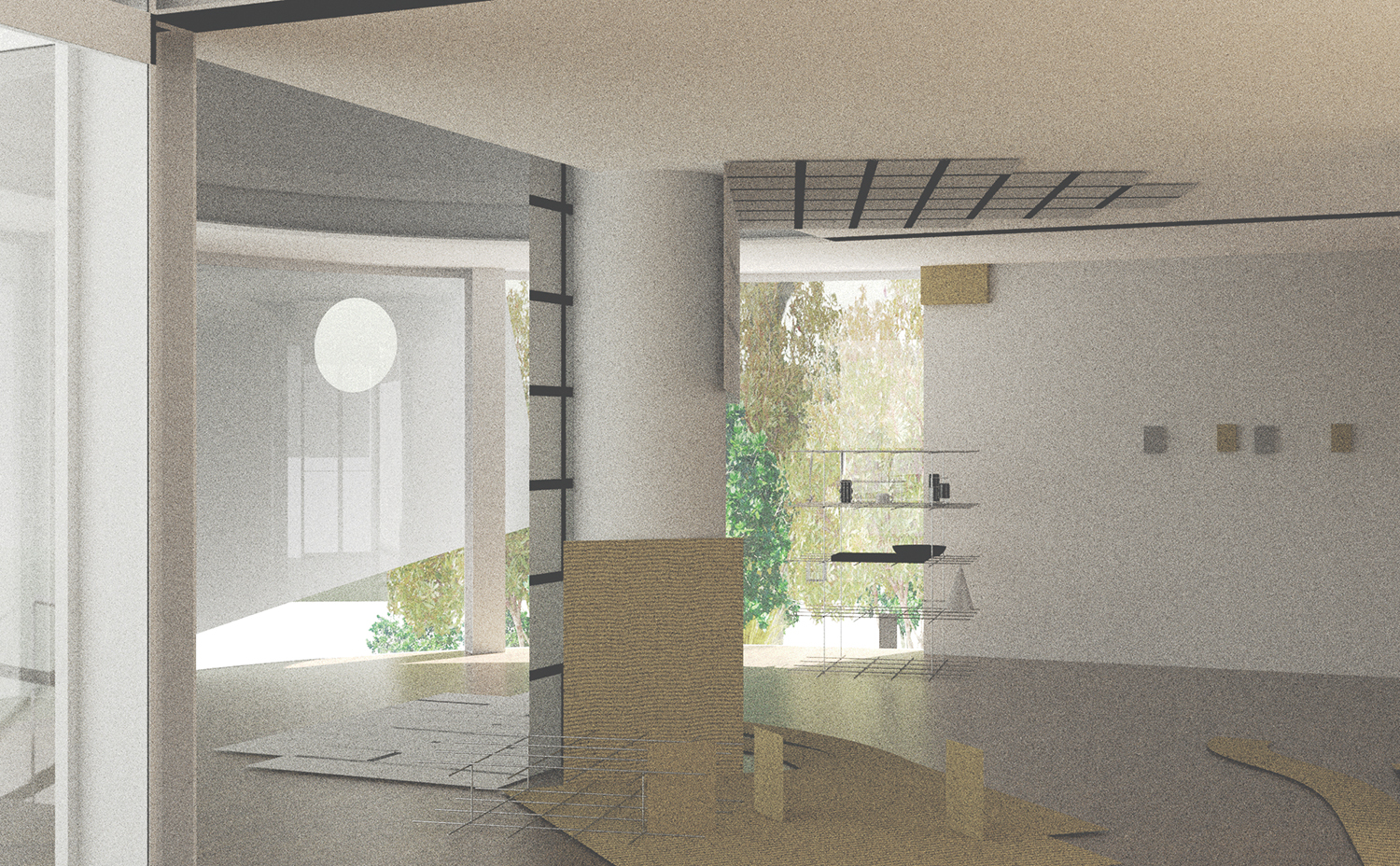

Rendering image plan of Overwriting, Overriding by Lee Dammy ©Lee Dammy

Kim Bokyoung: As mentioned earlier, the exhibition consists mainly of curatorial research and production, as well as commissioned works by participating artists. What roles do these two components play in the exhibition, and how does the toad function as a link between them?

Jung Sungkyu: It is important to start by describing each artist’s work. Lee Dammy (principal, Flora and Fauna)’s piece acts as a passage leading visitors into the exhibition. Rather than focusing on the nationalistic implications of the Korean Pavilion, she looks instead at the Giardini after the Venice Biennale closes, when the space is empty. She imagines a scenario in which microbes, trees, or cats (organisms that remain in the Giardini or the Korean Pavilion once people leave) become the pavilion’s ‘clients’. Her work speculates how the pavilion might be arranged if these organisms were to occupy it.

The other three artists begin with the Mancuso’s archive and the specific conditions of the Korean Pavilion as starting points, creating more direct connections to various points in the pavilion’s history. Among them, Young Yena (co-principal, Plastique Fantastique) approaches the ground beneath the pavilion from an archaeological perspective. Her installation will be in the pavilion’s basement and brick room, presenting a fake documentary that imagines an alternative narrative based on faxes and letters dating back to 1995, when the pavilion was built.

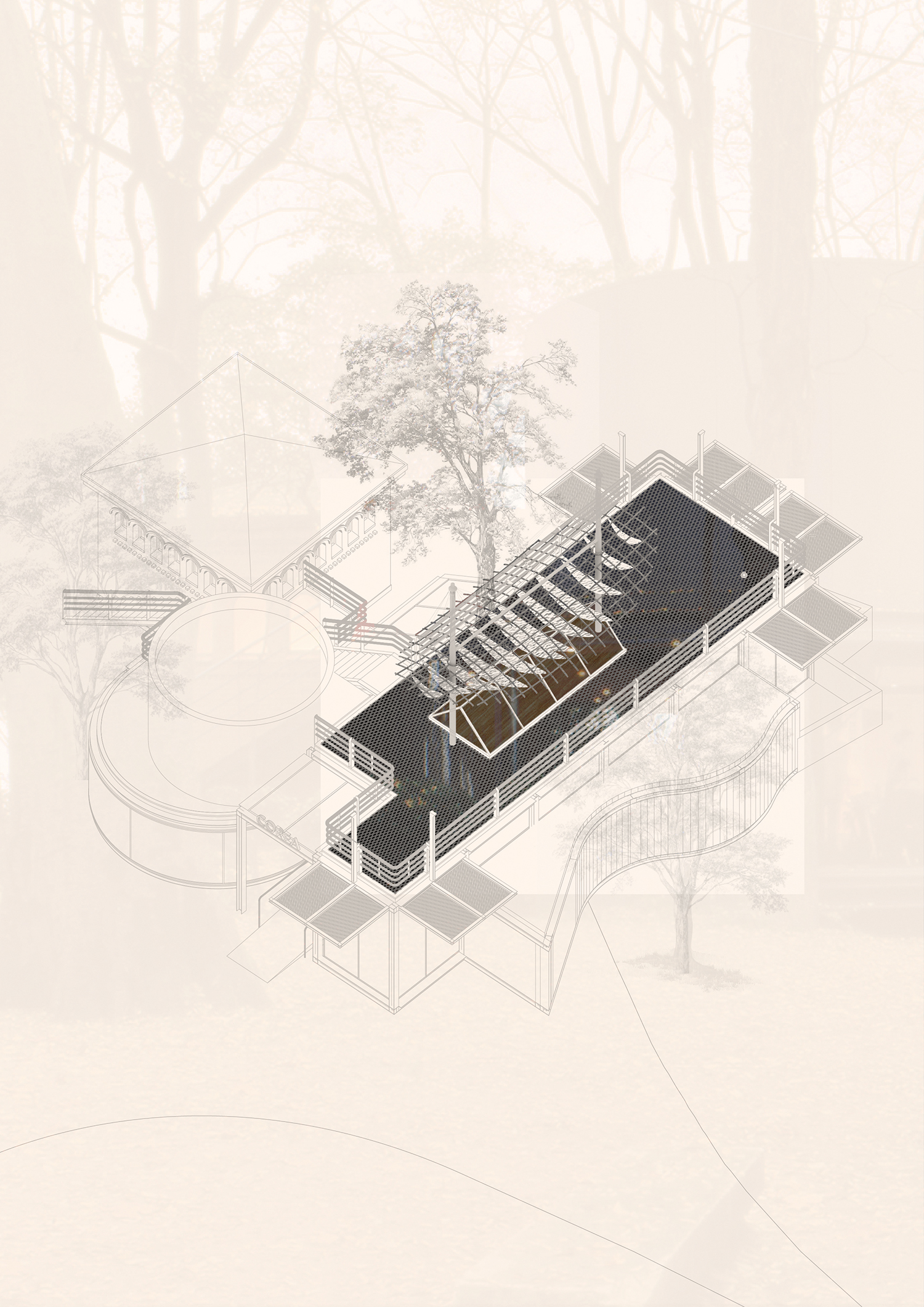

If Young focuses on the Korean Pavilion’s past, Park Heechan (principal, Studio Heech) focuses on the present. As mentioned, trees were a key element in the construction of the Giardini’s national pavilions (including the Korean Pavilion) and still shape the Giardini today. However, once the Biennale begins, attention usually shifts from the trees to the artworks. Park plans to use the pavilion’s transparency to redirect viewers’ focus back to the trees. Finally, Kim Hyunjong (principal, ATELIER KHJ)’s work is installed on the pavilion’s rooftop, a unique space in the Korean Pavilion, and this piece reactivates the roof as an exhibition area. In many other national pavilions, rooftop access is either severely restricted or near impossible. Through this installation, Kim visualises how the pavilion might expand in the future. We have designated the rooftop as a shared space open to other pavilions, envisioning the Korean Pavilion as a host that can facilitate collective conversations with its neighbours.

Chung Dahyoung: The exhibition is broadly divided into a documentary element and commissioned works, but it actually began with documentary components. However, we felt that relying on documentary elements alone was not enough to communicate our intention of looking at the Korean Pavilion – indeed, any national pavilion – from a fresh perspective. That is why we naturally decided to invite artists to create new works. Since we did not request any physical transformations, such as renovating the Korean Pavilion, the resulting artworks are imaginative in nature. They call attention to the longstanding shared heritage of land, trees, and sky, not only in the Korean Pavilion but also in other national pavilions in the Giardini. Through this process, we were able to consider broader issues such as how climate change affects Venice and the sustainability of the Venice Biennale.

Kim Heejung: In addition to the toad as a key motif, the curatorial team’s documentary video also serves as a unifying element throughout the exhibition. While examining the pavilion’s records and conducting site visits, we realised that interpreting the Korean Pavilion solely through the Mancuso’s archive would be incomplete. We decided it was necessary to maintain an objective stance toward the archive, and we apply the same approach when reviewing other materials. We made a conscious effort to reflect the curators’ perspective more actively, showing the context and progression of our overall project, and clearly explaining the diverse sources of our many materials so that the archive and the artists’ works connect effectively.

Image that shows the concept of 30 Million Years Under The Pavilion by Young Yena ©Young Yena

Kim Bokyoung: The Korean Pavilion’s rooftop was labeled ‘rooftop exhibition hall’ in the original drawings. It was used as an exhibition space in 2000, when its architect, Kim Seok Chul, also served as commissioner, and again in 2021. However, this is the first time in the Korean Pavilion’s history that the basement has been used as an exhibition space. How did you come up with the idea to display artworks there?

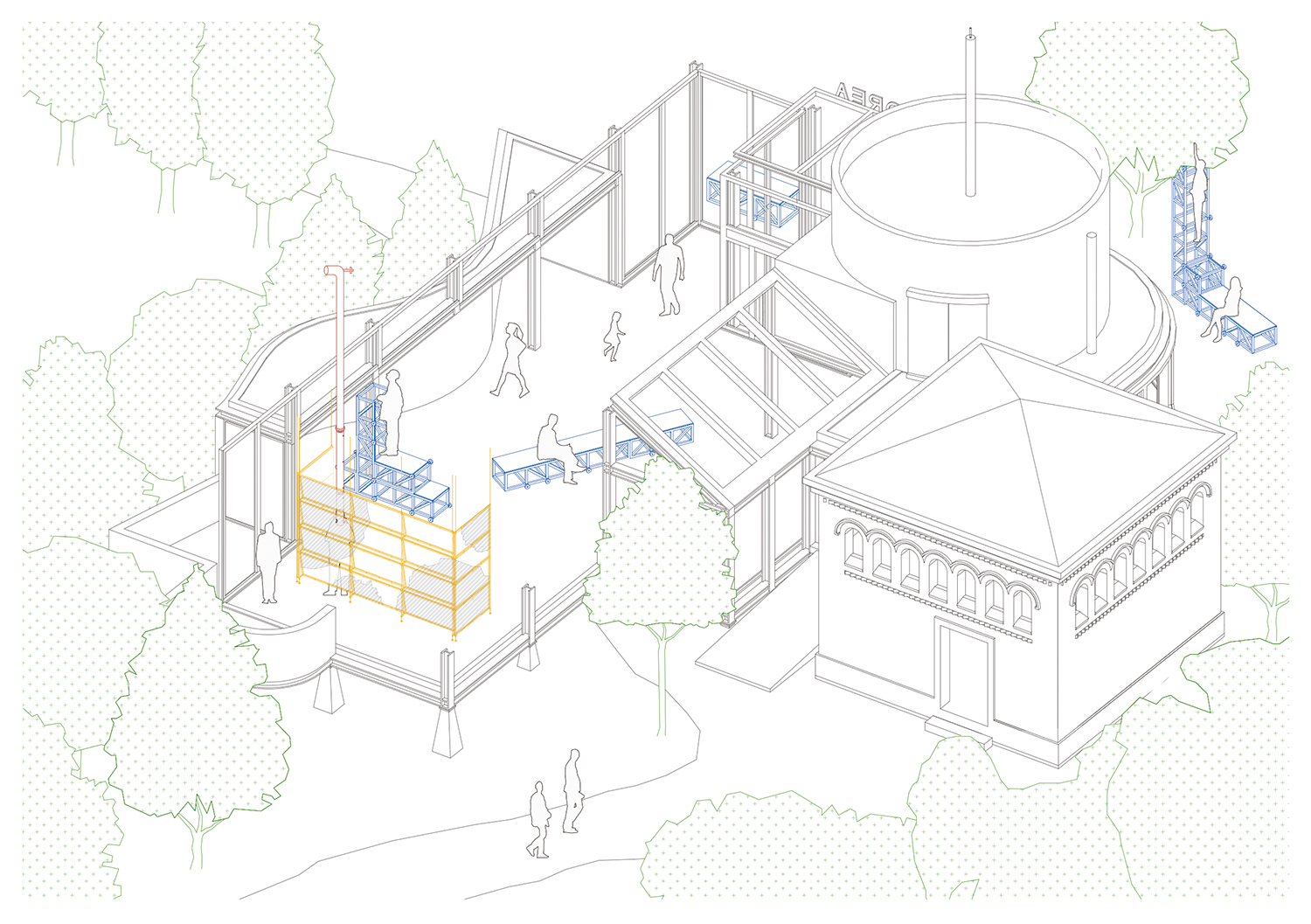

Chung Dahyoung: The Korean Pavilion is built on a lightweight steel frame with a pilotis. The positioning of each element has been strategically decided to highlight these original architectural features. Not only does the basement reveal the pavilion’s architectural character, but all of the artists’ works also draw attention to it. If you look at how the installations are laid out, both in plan and in section, you will see a strongly architectural approach as they move across multiple dimensions. This exhibition marks the first time that every part of the Korean Pavilion, including the basement, ground level, and rooftop, is being used as an exhibition space. It is also important that we have actively incorporated not only the interior but also surrounding elements such as nearby trees, treating them as integral parts of the pavilion.

Kim Bokyoung: Previous Korean Pavilion exhibitions often involved inviting multiple architects to showcase a series of architectural works or extending invitations to a wide range of artists, resulting in a very dense presentation of diverse perspectives. In contrast, the exhibition plan for ‘Little Toad Little Toad’ seems to allocate one exhibition room to each of the four architects, allowing for a more spacious arrangement. The curators also appear to reveal their intentions throughout the pavilion.

Kim Heejung: In line with our aim of re-examining the Korean Pavilion, we wanted to show as much of the pavilion itself as possible in this exhibition. Rather than adding something to the curved floor plan and transparent façade, we decided to present them as they are. Kim Giseok (principal, Spatial Semiology), the exhibition designer, did not build any large temporary structures to divide the space. Instead, he created devices to help visitors better understand the existing space. You could say that this exhibition design is almost another commissioned work.

Chung Dahyoung: Think of it as creating captions. Since the Korean Pavilion is our main subject, we are placing it on display and captioning it accordingly. To add a bit more explanation, showing the Korean Pavilion ‘as is’ does not mean leaving it completely empty. We wanted to reveal spatial elements and hidden meanings that have not been obvious when viewing the Korean Pavilion in the past. Through the works produced by the curatorial team and the commissioned pieces by the artists, we aim to bring features like the basement and rooftop into view, as well as focus attention on natural elements around the pavilion. We expect Kim Giseok’s designs to act like prostheses that encourage visitors to explore every corner of the Korean Pavilion.

Plan of Time for Trees by Park Heechan ©Park Heechan

Kim Bokyoung: From what you’ve described, this exhibition at the Korean Pavilion sounds highly site-specific. I understand there will be a return exhibition in Korea next year, which seems like it might be challenging in terms of how to structure it.

Kim Heejung: It would be difficult to replicate the exhibition at the Venice exactly as it is at the Arko Art Center while preserving its original context. That is the limitation of site-specific work. We are including the exhibition process in the documentary video shown in Venice, so we will probably add footage of the onsite exhibition to that video for the return exhibition in Korea. It will be a kind of reporting exhibition.

Kim Bokyoung: Finally, if there is something you hope to achieve with this exhibition or something you feel you have already accomplished, please let us know.

Kim Heejung: First, I want to present a different kind of exhibition that is organised by a professional collective of architectural curators. I hope this exhibition becomes a turning point so that more people, regardless of age or level of experience, can participate in the Venice Biennale. Also, although it has been 30 years since the Korean Pavilion was built, there have been no thorough records that allow us to fully understand it. Its history has mostly been passed down through oral accounts. We spent a great deal of time verifying these details for this exhibition, and we are still in the process of doing so. I hope this exhibition serves as a guide for writing and interpreting the history of the Korean Pavilion.

Jung Sungkyu: I would also add that working on these commissioned pieces with the artists was incredibly meaningful. All the participating artists are from our generation, and each of them has lived and worked in various countries. This led to very interesting conversations as we developed their work. It was fascinating to see the diversity amongst these artists, and I was impressed by how we ultimately chose to arrange their pieces through mutual coordination. During the planning process, I often found myself wishing to introduce these artists more broadly.

Chung Dahyoung: I agree. Re-examining the Korean Pavilion is the most important point, but I hope it also becomes a chance to rethink the Giardini and the Venice Biennale as a whole. Personally, I have always felt a disconnect between archives and commissioned works, but I think we found a way to bridge that gap through this exhibition. As a curator, I see that as a major accomplishment.

Plan of New Voyage by Kim Hyunjong ©Kim Hyunjong