SPACE March 2025 (No. 688)

MIKALON Bike

Hybrid folding method with a separable mechanism

Interview Roh Ilhoon principal, Studio IL HOON ROH × Lee Sowoon

Architect and designer Roh Ilhoon attends to experimental furniture and installation work driven by a structural approach. His aesthetic objective is to explore how nature develops its own optimal forms and to reveal their excellence and beauty by reinterpreting them as architectural sculptures. Although it has not been publicly revealed until now, he has been working on a bicycle project entitled MIKALON since 2018. He has captured the structural ideas he has been researching for over ten years in the form of a bicycle. MIKALON, which began as a ‘moving exhibition’ and ‘a work of art that can be used every day’, has completed its years-long preparatory process and is set for an official overseas launch this April.

Lee Sowoon (Lee): I’m curious about what led you to stop practicing architectural design and begin producing artworks.

Roh Ilhoon (Roh): When I studied and practiced architecture, I conducted a lot of experiments. Those experiments weren’t about making models but rather about visualising structural ideas or aesthetic goals. I believe that is the purest form of architecture. However, actually building a structure involves financial and technical limitations. For instance, if a particular structural method requires a budget of one billion KRW to be realised in full, but you can do it for one hundred million KRW using concrete, then you’re forced to choose the more economical method. That inevitably weakens its fundamental integrity. It’s only natural, and it might be part of the realisation process, but I found it distressing. I like forms found in nature, such as waves, ripples, lightning, or the patterns of Earth’s magnetic fields. About fifteen years ago, I had numerous ideas regarding structures that draw upon these perfect shapes generated by nature. I thought about creating architectural sculptures to express these in their purest possible state. However, I also felt that the format had to be something people could buy and sell to establish a virtuous cycle, so I chose furniture. My first work was Fabric Table R (2007), made by pulling fabric taut. After finishing it, I realised there was already a demand, a market, and a genre under the name design art.

Fabric Table R (2007) ©Kim Junghan

Lee: After moving on from furniture, why did you elect a bicycle on which to focus?

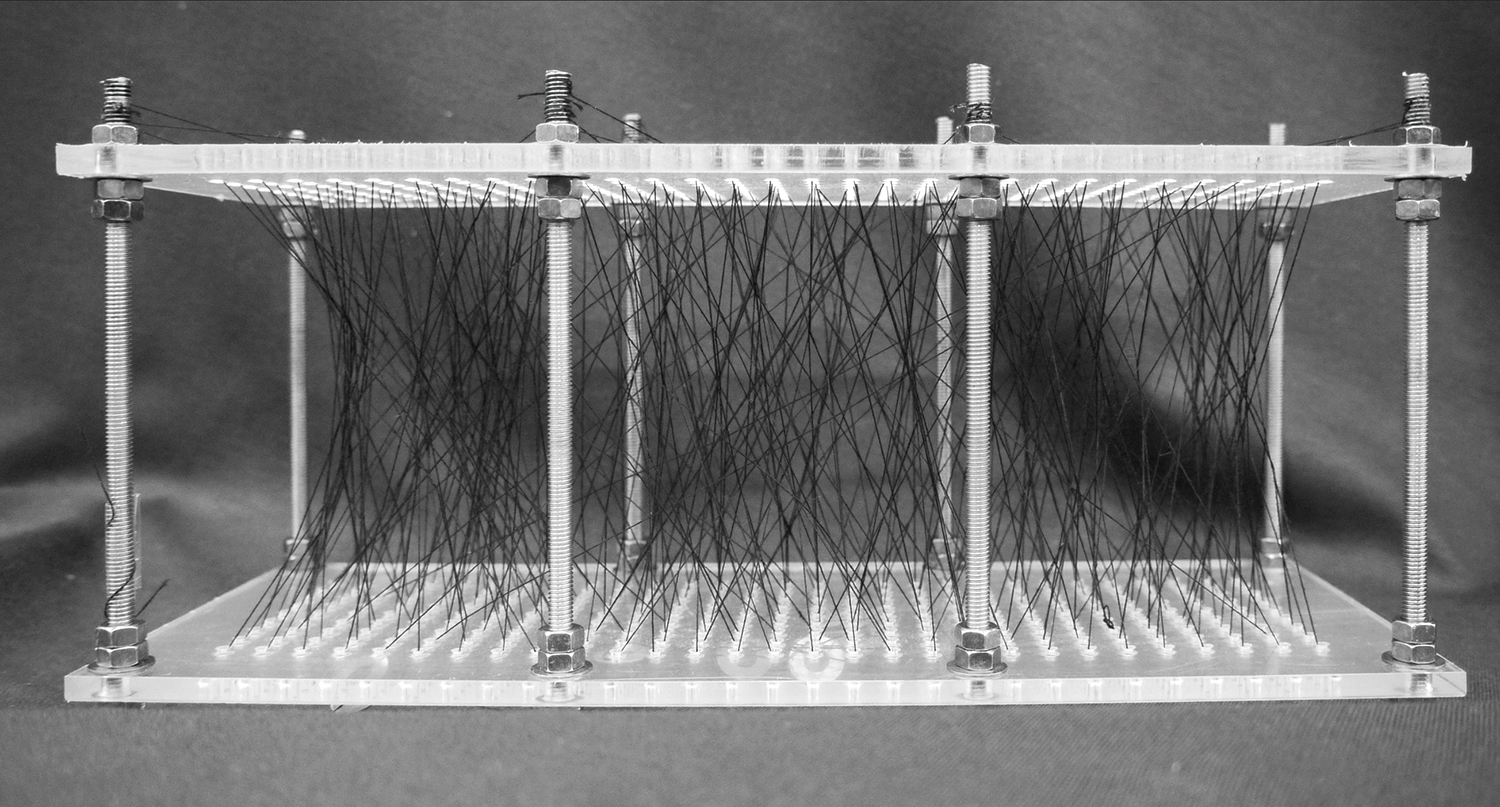

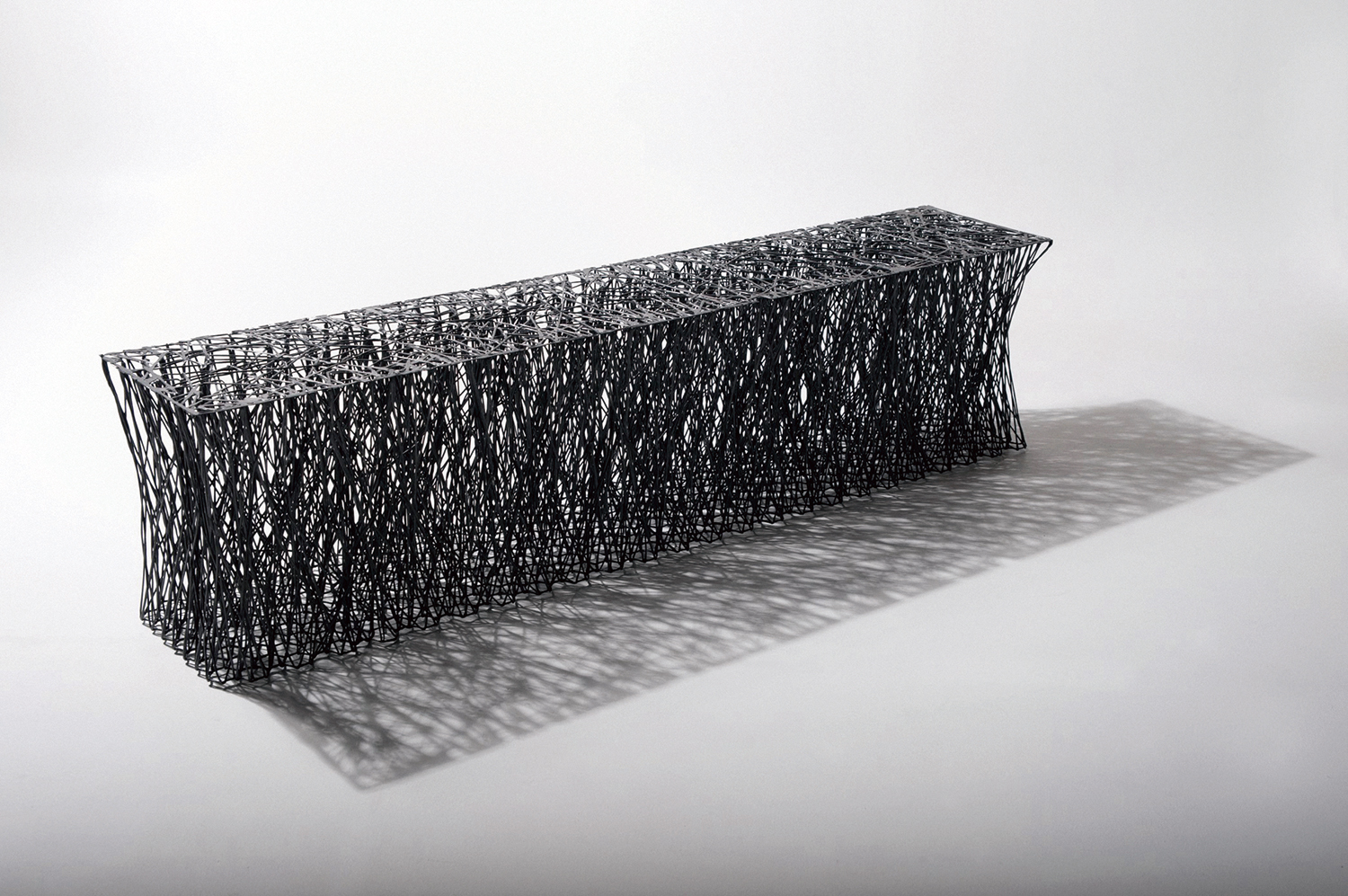

Roh: Over the eight years I focused on art projects, I held several exhibitions. But exhibitions require physical space and last only for a limited duration. I wondered how I could break free from those constraints of time and place to create more points of contact with the audience. Archigram’s Walking City (1964) keeps moving around and exhibiting. Wherever it stops becomes the exhibition space—and potentially a festival. Wondering what might serve a similar purpose or function led me to the idea of a bicycle. The works I’ve presented so far are about imitating and physically realising the harmony and forces observed in nature. In nature, the ‘correct’ shape is never predetermined; forms emerge progressively through certain rules, eventually arriving at an optimal structure. If you look at the human bloodstream, vessels intersect, form nodes, and branch out. The same phenomenon occurs in all things that branch out in nature—bones, river streams, and lightning. They organise themselves to distribute force most efficiently, using the least amount of material. I imitated this principle in Rami Bench (2013). When thin threads of twisted carbon fiber intersect, each angle adjusts minutely as they are pulled, and that angle itself is the most efficient shape for transmitting force, and so it changes accordingly. I believed there was beauty in that, but it didn’t seem to have been communicated very well to audiences. When you place furniture in an exhibition hall and explain the natural forms and principles it uses, most people say, ‘I had a nice cultural experience’, but that’s about it. Because it’s art that doesn’t directly affect them, it’s soon forgotten once they leave the exhibition space. Strictly speaking, that happened because I chose furniture as my medium. There’s no pressing need for furniture to be extremely lightweight while maintaining a high level of rigidity. But a bicycle is an entirely different story—weight and rigidity are everything. If I apply the beauty of natural structures to a bicycle to which anyone can relate and even accomplish something that existing bicycle manufacturers have been struggling to achieve, it becomes a kind of proof. Plus, when you ride the bicycle, the road itself becomes the exhibition space, and everyone who sees it becomes the audience. That’s why I felt it was a viable format.

Lee: MIKALON is a sister project to the Rami series. How has Rami’s structural idea been applied to the bicycle frame?

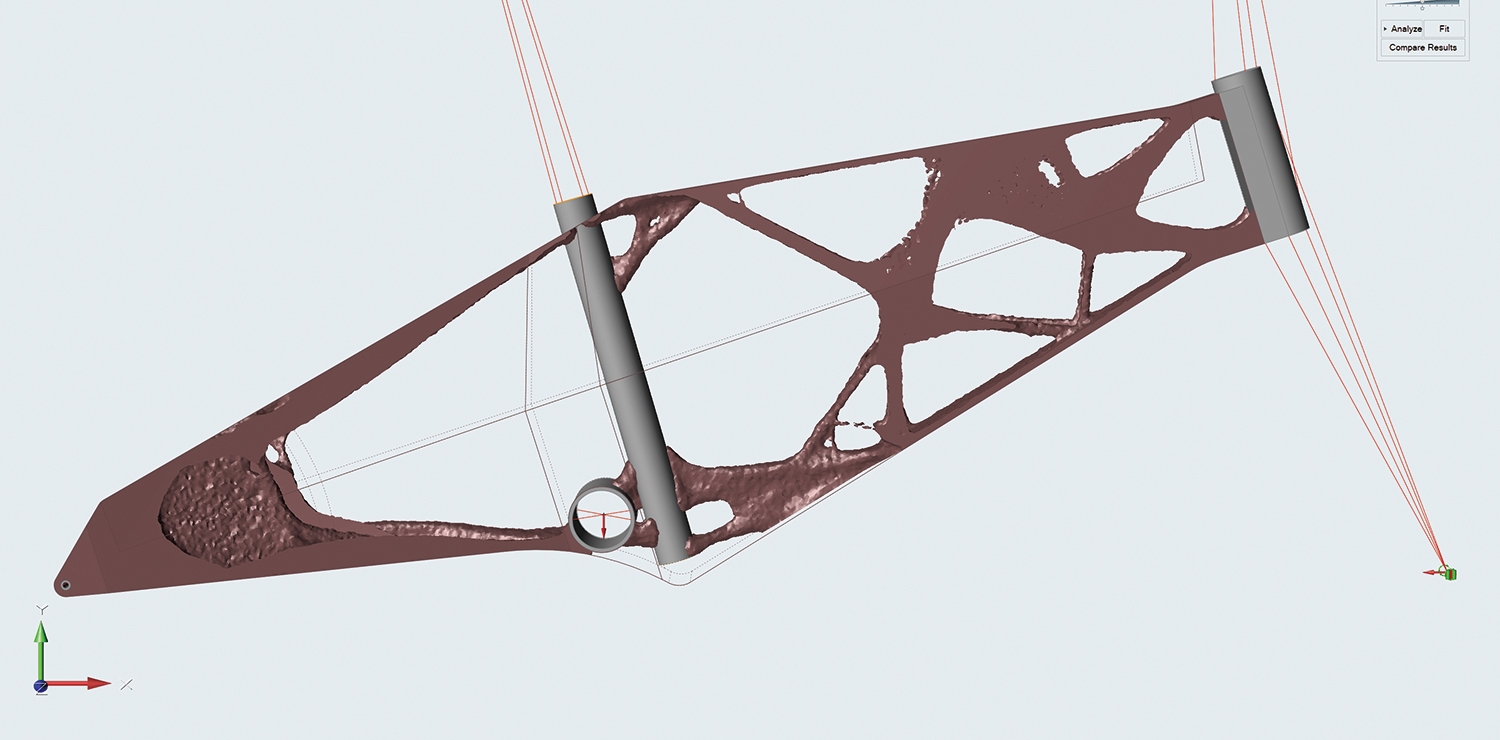

Roh: The core idea of Rami is that when sloppy threads intersect and are pulled, the angles self-adjust to reach an optimal structure. But a bicycle frame has fewer nodes, so it’s theoretically much simpler. At the earliest stages, I pulled threads to experiment, and then tested them in a virtual environment. There’s a programme called Inspire, made by Altair, which performs structural calculations in the same way Rami does. It uses mathematical processes to leave material where the force is heavy and eliminate it where it’s weak. Just as threads in Rami intersect and pull at one another to find the optimal angle, Inspire removes unnecessary elements to produce a branching and spreading structure in a natural way. Using simulations, I identified a frame shape optimised for the flow of force and then converted it into a form that could actually be built. This approach contrasts with the method people usually describe as ‘optimisation’. A civil engineering department at a certain university in Japan once tried designing an optimised structure to withstand earthquakes. They started with a cube, simulated an earthquake, and repeatedly reinforced weaker areas. After a few generations, the structure ended up looking like honeycomb. MIKALON, on the other hand, starts with a shape that’s already optimised and then seeks a way to realise it. Using the former approach might yield a similar result after fifty generations, but we effectively took a shortcut. Antoni Gaudí and Frei Otto both employed such approaches in architecture. In the existing bicycle industry, a diamond frame – composed of triangles – has been the standard working method for achieving both lightness and rigidity. This approach localises higher stress in certain areas, so you reinforce those while shaving off material elsewhere to reduce weight. Over the decades, repeated attempts have been made to gradually optimise these frames. MIKALON, however, had no preconceived premise of a triangular structure; we calculated where it should branch out from the start, which made structural innovation possible.

Bespoke titanium parts ©Roh Ilhoon

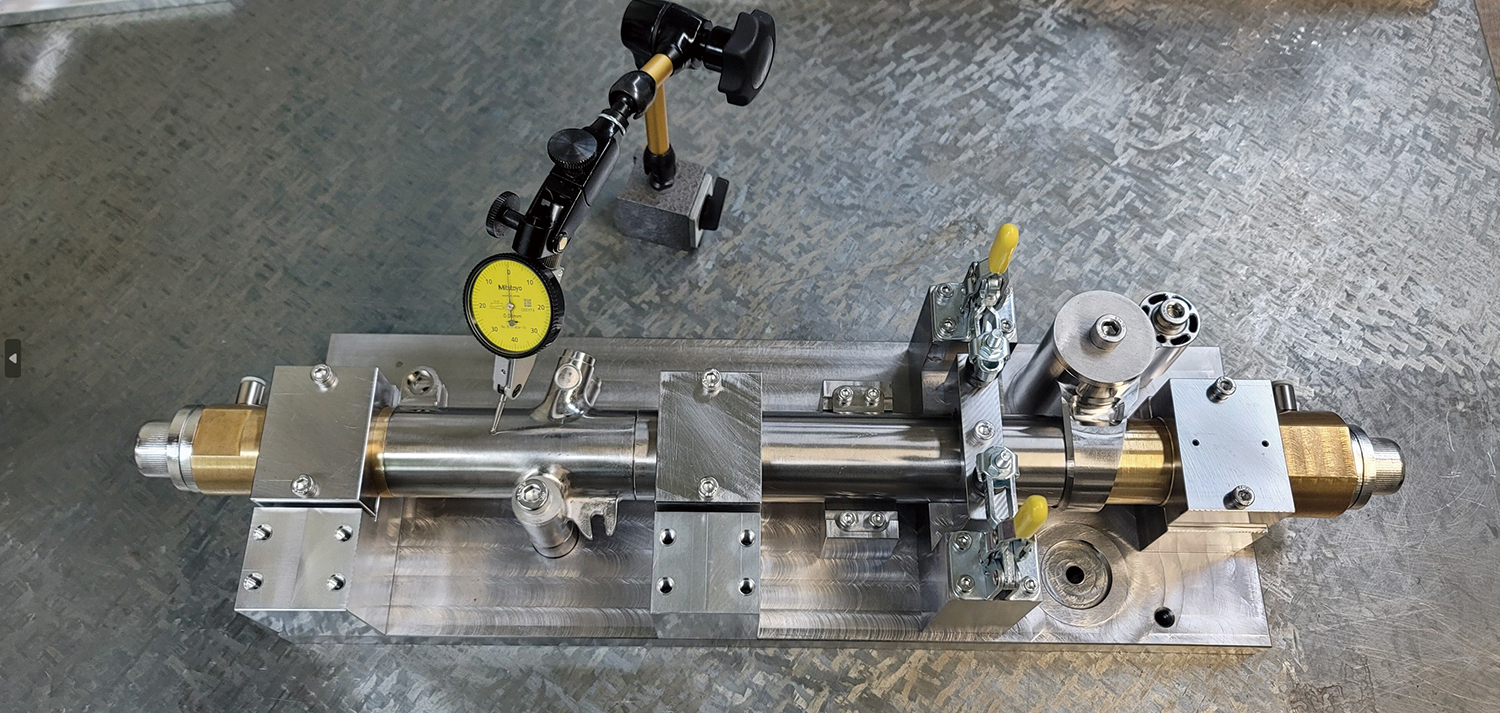

Bicycle Manufacturing Jig ©Roh Ilhoon

Lee: If you’d already derived an optimised frame shape at the initial design phase, it seems you could have simply 3D printed it.

Roh: I did consider 3D printing at first, but that manufacturing method is prohibitively expensive, reducing accessibility. The reason I started this project was to step away from cultivating an artwork that would sit idle in a museum; the bicycle had to be something that could run on real streets. It couldn’t just be a prototype—it had to be mass-producible. From the start, I was determined not to make a ‘concept bike’. I had to reach at least the level of existing bicycle manufacturers and engineers. Then I added the feature of fitting it into a carrier. The reason we released it as a folding form is also tied to regulations, specifically freedom from the bicycle oversight rules of the UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale). Normally, frames aren’t allowed to have joints, but folding bicycles are an exception. By making it folding (and partly separable), I could preserve the structural idea of Rami in its pure state while still being recognised as ‘legitimate’ by the existing bicycle industry. After thousands of simulations and our own design and manufacturing processes, we made true mass production possible. MIKALON weighs under 9kg, and for the single gear version, it’s 7.8 kg—making it the lightest in its class worldwide. It could get even lighter. When I participated in Eurobike, a bicycle expo in Germany last July, people were amazed by MIKALON’s weight. That means my message was being conveyed through the bicycle itself.

Lee: Instead of a standard folding bike design, MIKALON uses a hybrid approach that combines a separable mechanism and a folding method. Does that have something to do with the shape of its frame?

Roh: The main goal of the MIKALON project was to find an optimal frame structure, and so making it compact was secondary. In most folding bicycles, you figure out the folding mechanism first, then reinforce the structure afterwards. But with MIKALON, we decided on the bike’s overall shape first and only then thought about making it more compact. When we tried to turn it into a folding bike at that stage, the original idea no longer worked. So, we came up with a new approach. We fully separated the frame, then added one more folding method on top of that.

Inspire Simulation from Altair ©Roh Ilhoon

Initial sketch for production conversion ©Roh Ilhoon

Lee: It took eight years before MIKALON was ready for release. What challenges did you face?

Roh: Initially, I thought it would take at most a year, but it ended up taking eight. I had a similar experience with the Rami series. I contacted various companies that handle carbon fiber, asking them to manufacture those shapes, but many said they didn’t have the means to produce such forms. In the end, I had to develop everything myself, from the materials to the fixtures that hold the threads. If you have an idea but no way to realize it, you have no choice but to discover the manufacturing method yourself. The same thing happened with the bicycle. MIKALON’s numerous nodes made it impossible to build using existing processes suited for standard frames. An ordinary diamond frame just consists of two triangles, front and rear. If architecture can tolerate around 12mm of error, a bicycle has a much smaller scale and therefore demands a different level of precision. Some components can’t exceed 0.02mm of tolerance, or the bike will warp. I worked with three overseas bicycle manufacturers and attempted to produce prototypes in Italy and China, but all failed. Ultimately, I concluded that I had to do it myself. When meeting with bicycle companies, I picked up a lot of know-how, mainly regarding how to control thermal expansion during welding. Once I understood the finer points, I could apply it to my own production. Three years ago, I enrolled in a welding school for three months of practice. I even built my own welding jig to prevent the frame from warping. Jigs, moulds—ultimately it all comes down to fixtures. In fact, the main idea behind the Rami series is not so much in the final product as it is in the fixture itself, because all parameters are controlled there. It’s the same with bicycles. From analysing the reasons for our previous failures, I realised it always came down to the fixture. Once I took it into my own hands, our precision increased exponentially, and we finally reached a level where production was feasible.

Lee: How do your studies in architecture and your experience practicing it connect to your current way of working?

Roh: There’s no difference from when I was working on architecture. At Foster + Partners, I designed everything from shadow gaps and door handles to elevator buttons and even bathtubs. Interestingly, having many details is an advantage when it comes to bicycles. Almost every bicycle maker has its own special bolt detail since the ideal solution varies depending on the frame. In some cases, companies obtain patents so others can’t use their designs. For MIKALON, nearly all components, from bolts to nuts, were newly designed and went through an optimisation process that factored in machinability, resulting in custom-manufactured parts. It’s 100% bespoke. That detailed process – like designing a fire hydrant cover in architecture – is exactly what I’m doing now with the bicycle.

Experiment for Rami Bench ©Roh Ilhoon

Rami Bench (2013) ©Kim Junghan

Lee: How do you currently define your design identity?

Roh: I can say with certainty that I’m an architect. I firmly believe that architecture doesn’t have to be a building. Architecture is inclusive and highly expandable. Was Michelangelo an architect? Architecture used to be one branch of art, and in those days, there wasn’t even a separate profession known as an ‘architect’. As technology advanced, we needed sophisticated engineering knowledge, and that gave rise to the architect’s professional domain. Interestingly enough, as technology keeps developing, even engineers can’t do all the calculations anymore—they’re so complex that we rely on computers, and now we even have AI. In a way, the tools have become more accessible to everyone. As complexity increases, it subdivides into specialised fields, but once it increases beyond a certain point, it seems to merge again under the name of ‘creation’. That’s my perspective. In contemporary architecture, its boundaries and definitions have become more ambiguous. Is what Archigram did thought of as architecture? Is pitching a tent in the desert architecture? I decided there was no need for strict definitions. What I learned in architecture doesn’t have to be confined to designing and erecting buildings. Right now, I’m making bicycles, but the techniques and know-how I learned from architecture still influence everything. I believe all my work is architecture.

Lee: What are you thinking of making next?

Roh: MIKALON is just the beginning. I’m planning to establish MIKALON Lab in the mid to long term. If you go to a bicycle show, you see countless items – shoes, glasses, helmets, and so on. It’s a massive industry. In MIKALON Lab, I want to apply a ‘MIKALON-isation’ to all of that. Bicycles, like architectural details, have no limits. They naturally continue to evolve as new materials, functions, and technologies emerge. I will also continue creating furniture and installation works. Although I’ve been focusing on bicycles lately, I have been preparing artwork as well. This June, I’m unveiling a collaboration with master weavers of tapestry in Aubusson, France.

Separated frame

Patented cable separation device separate & reconnect the brake cable in seconds