SPACE June 2025 (No. 691)

A Tropical Alpine City with No Time Difference: Aileu, Timor-Leste

If one were to trace a line southward from Korea (36° N, 127.7° E), one would arrive near the equator at Timor-Leste (9° S, 126° E), the only country in Asia located in the southern hemisphere. Owing to this near alignment of longitude, Korea and Timor-Leste share the same time zone, despite being hemispheres apart. Since 2017, the Sisters of the Blessed Korean Martyrs have been caring for local children and offering educational support to young people in Aileu, a mountain town roughly an hour southwest of the capital. Our involvement began when we were invited to design a convent with a chapel and dormitory for girls to serve the sisters dispatched to this remote region.

A Convent Within Light, Wind, and Trees: Taking Comfort in Rain and Heat

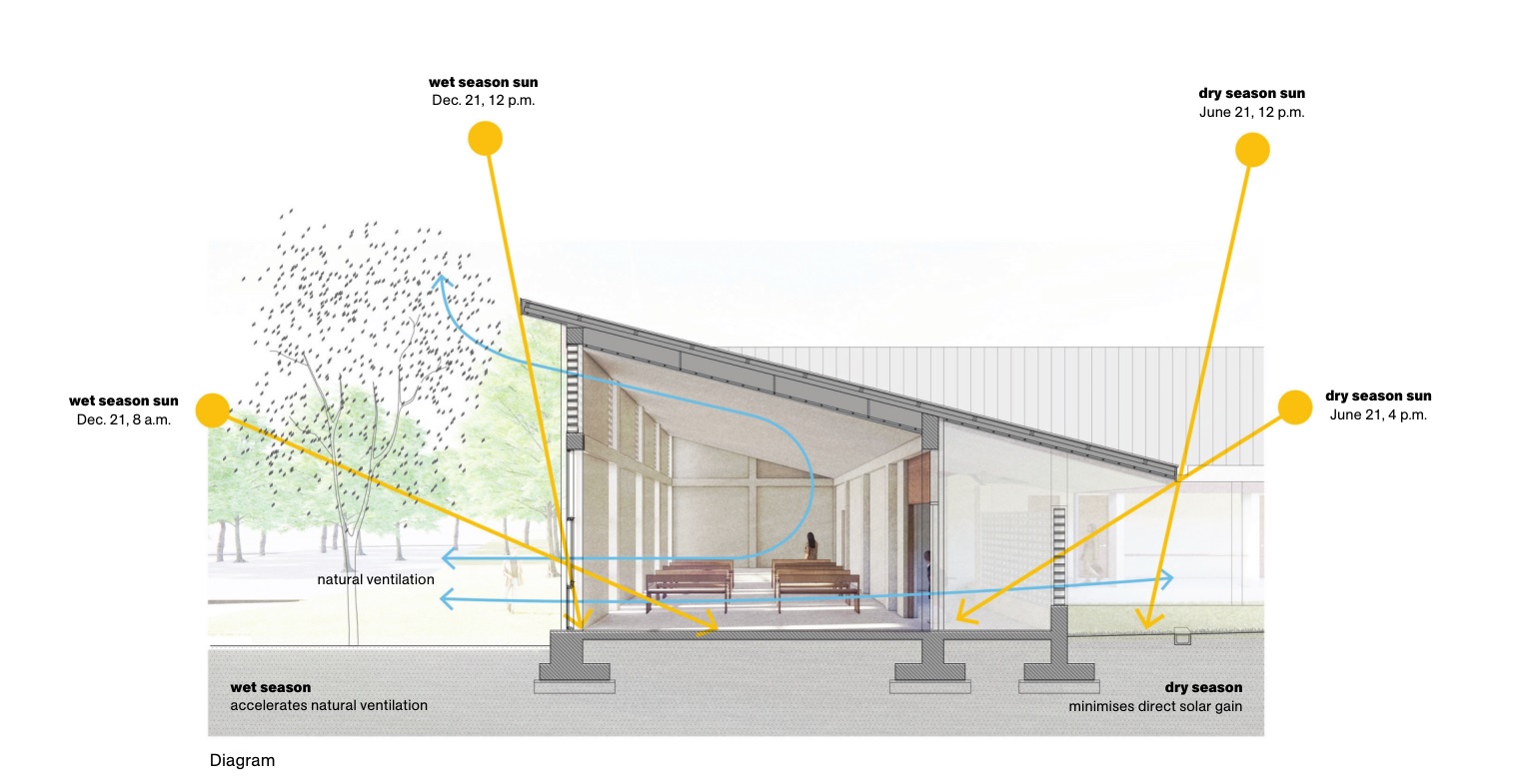

To those accustomed to the urban climates of the Northern Hemisphere, the most unfamiliar aspect of Aileu was its weather. Timor-Leste, situated in the tropics, experiences a pronounced alternation between its wet season (from December to April) and dry season (from May to November), marked by high temperatures and humidity. Aileu, at over 1,000 metres above sea level, required a means of enduring the heat and humidity during the monsoon as well as the intensity of the dry season sun. With electrical and water infrastructure still unreliable in the region, we chose to eschew mechanical systems and instead return to architectural fundamentals, focusing on the relationships between light, air, and space. The sun’s path, which varies significantly over the year, offered a new framework for understanding light. Unlike in Korea, where the sun always traverses the southern sky, Timor-Leste’s position near the equator means the sun rises and sets from the northeast to northwest in the dry season, and from the southeast to southwest in the wet season. After simulating the solar trajectory throughout the year, we oriented the chapel’s façade southeastward and introduced clerestory windows. This design allows the early morning light of the wet season (beginning in December) to penetrate deep into the interior, warming the air and triggering a stack effect that promotes natural ventilation through operable windows on either side of the chapel. During the dry season, deep overhangs and covered corridors protect interior spaces from the harsh, direct sunlight. The convent site, nestled at the base of a forested hill, featured several mature trees, including mango trees, with elegant forms. Rather than felling them, we arranged the convent and dormitory buildings around these trees, preserving their shade and sense of presence. A particularly large tree at the entrance now anchors the entire spatial composition, allowing the newly built structures to seamlessly merge into their natural surroundings from the moment of completion.

©Kim Namjoo

Simplicity, Executed with Precision and Purpose

Engaging with the materials and construction techniques available locally proved to be as instructive as it was humbling. In Timor-Leste, construction labour is often unstructured—workers may appear on site in slippers and building systems lack the rigour or technical refinement seen elsewhere. Yet it was precisely these limitations that compelled us to reconsider assumptions typically taken for granted when resources are abundant. The architecture needed to be safe and cost-effective, with minimal transportation of materials, and clear enough in its drawings to be easily understood by all. Accordingly, we opted for simplicity: straightforward structural systems, locally sourced materials, and intuitive detailing that would lend itself to on-site comprehension. Rather than diminishing the project, this constraint became a strength. The convent was designed as a single-storey reinforced concrete structure with exposed columns and beams. Long, slender windows were placed between columns, allowing light to filter gently through, casting shapes that echo a criss-crossing rhythm that is serene and contemplative. To ensure privacy in the sisters’ residential quarters, we introduced a screen wall around the central courtyard, using cement blocks manufactured locally. Choosing the right size and pattern became a communal task: the sisters visited nearby factories, took photographs, and returned to discuss and select the most suitable blocks together. In this way, the architecture, while formally modest, became a canvas upon which the textures of the equatorial light could be projected. With each passing season, the quality of light shifts, casting a dynamic and ever-changing atmosphere across the interiors. A subtle difference in levels between the private living quarters and the more public chapel and lounge allowed for spatial separation while still sharing the same courtyard. The low-pitched gabled roof of the residential wing echoed the traditional roofs of Aileu, while the higher-sloped roof of the chapel and lounge lent the building a quiet prominence. When one stands in the courtyard and looks towards the chapel’s roofline, the sky of Aileu stretches beyond; open, luminous, and ever-present. Today, the convent is home to three Korean sisters, two novices, and three lively dogs.

A Girls’ Dormitory Designed for Gatherings

Situated in Aileu, The Convent of Sisters of the Blessed Korean Martyrs in TimorLeste represents a thoughtful and deeply rooted response to the realities of postindependence Timor-Leste, one of the world’s poorest nations and a country still in the process of establishing a comprehensive educational infrastructure. Here, the physical remoteness of villages and the dangers associated with long-distance travel have long hindered girls’ access to consistent schooling. In recognition of this, the Sisters of the Blessed Korean Martyrs created a girls’ dormitory as a place of safety, learning, and to offer a community for young women from outlying areas. The dormitory is composed of two elongated buildings placed in parallel. One houses communal facilities such as study rooms and a kitchen; the other, the living quarters. With only limited financial means, the design had to be stripped of all but the essentials. Yet it was clear that these adolescent girls would need more than functionality; a space for conversation, laughter, and shared solace seemed just as vital. Thus, a series of modest courtyards, stepped and partially sheltered, was introduced in the interstitial space between the two wings. In doing so, architecture itself became an instrument of community. Each morning and evening, the students gather in these small courtyards to pray together. In the afternoons, the same spaces come alive with chatter and laughter, and at times, the harmonious singing of songs taught by the sisters. Today, the dormitory is home to around twenty girls, each of whom inhabits not just a building but a shared life. This project, shaped as much by the material and climatic constraints of TimorLeste as by the needs of its people, began with a reading of the landscape and evolved into a celebration of its culture. It is our hope that the convent continues, for many years to come, to serve as a place where learning, sharing, and belonging are nurtured – quietly, but profoundly – within the embrace of its community.

Kim Namjoo (University of Seoul) + Kim Eunbee (dir

Aileu, Timor-Leste

religious facility, dormitory

10,417.4m²

convent – 851.2m² / dormitory – 521.8m

1,373m²

1F

6.45m

13.17%

13.17%

RC

water-based paint, colour steel panels

water-based paint

Yeo Deukhyeon

XTRUTURA, LUZ, CONSTRUÇÕES

Jan. 2021 – July 2022

July 2022 – May 2024

Sisters of the Blessed Korean Martyrs